On the day that Broon, fluttered his eyelash, gave big Barak a comehither wink and proclaimed himself the big man on campus, an American journalist wrote something akin to a piece of journalism, we in Scotland have long given up on. An impartial article. Read on and applaud.

* For lurking dependence junkies, be aware that you are being insulted, you just don't know by how much.

ONE OF THE most interesting politicians in Europe these days is a Scot, and I don't mean Gordon Brown. Alex Salmond is the first minister of a devolved Scottish parliament, a creation of Tony Blair's Labor government designed to take the wind out of Scottish separatist sentiments.

A few years ago, however, a ranking member of the British royal family, whose members aren't supposed to get involved with politics, committed an indiscretion by telling me that he thought devolved parliaments were a terrible idea because they could break up the United Kingdom. The Welsh would stay with England, and maybe the Northern Irish, he said, but the Scots probably would not. Salmond, the head of the Scottish National Party, is banking on the royal being right.

After centuries of fighting the English to maintain independence, the two thrones were united when James VI of Scotland became James I of England in 1603, after Elizabeth died childless. In 1707, the two countries were joined under one parliament - the one in London. For the next 300 years, Scotland helped build the British empire, contributed more soldiers per capita to Britain's wars than any other region, invented more things, and had more than its share of prime ministers. Edinburgh became the seat of the Scottish enlightenment, a remarkable burst of creative energy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. But something of William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, and the independence of yore lingered in the Scottish heart.

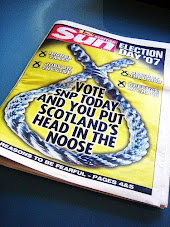

Ten years ago, Scotland got its own parliament back, with limited powers. Defense and diplomacy are in London's hands. The Scottish National Party won the election of 2007 by a whisker. Some thought the Scottish Nationalists' minority government would fail, but it hasn't. Neither has Salmond, whose rapier repartee is often on display in the parliamentary put-down that Britons love.

On a recent visit to Edinburgh, I met the first minister in his office in the new Scottish parliament, a startling architectural statement in the tumble-down modern style. An economist by training, Salmond is a big admirer of the late John Kenneth Galbraith and began quoting some of his work from memory.

His plan is to get a referendum on Scottish independence before the people sometime next year. Polls don't show a majority of Scots ready for independence yet, but Salmond believes that they do want the choice. Getting a bill passed on a referendum will be difficult because neither Labor, nor the Tories, nor the Liberal Democrats want any such thing. During my visit, the Scottish edition of the Times of London revealed that in the 1970s the British Labor government went so far as to redraw the boundaries of North Sea oil to deprive Scotland of much of it, and even contemplated stirring up separatists movements in the Scottish isles of Orkney and the Shetlands, should Scotland go independent, to deprive Scotland of even more oil.

Salmond says the nations he looks to for inspiration are Ireland for its lower corporate taxes, the recession notwithstanding; Norway for its stewardship of oil revenues; Finland for education; and the region of Catalonia in Spain for its emphasis on cultural identity. In general, "I tend to like the Scandinavian societies," he said, for the way they balance freedoms and social responsibilities.

Salmond's independent Scotland would keep the monarchy and the English language, although efforts are being made to keep Scottish Gaelic alive. Salmond himself uses old Scots, the language of Robert Burns, when he feels the need to tweak colleagues in the British parliament in London where he also sits. "They know they are being insulted, but not how much," he says.

The SNP's nationalism is based on citizenship, rather than on ethnicity, religion, or language, and is pro-immigration; quite different from many national movements.

Scotland's two biggest banks, Royal Bank of Scotland and Halifax Bank of Scotland, are in deep trouble, but Salmond hopes that even in recession Scots would prefer to have the "same economic teeth" that other nations have, rather than "hang on to the United Kingdom treasury."

Scotland's near neighbors, Ireland, Iceland and Norway, all became independent in the 20th century. Salmond is hoping that Scotland will come into its own early in the 21st.

H.D.S. Greenway's column appears regularly in the Globe.

Rockin' Roddy Piper Hoo haaa!